by Per Gade

Paul Weschke’s career was interrupted first by WWI and then when he was retired, WWII. He died in 1940, the 1st year of WWII. Anton Hansen, solo trombone in the Royal Orchestra, Copenhagen, used to send him food parcels from Denmark. He had been forced to join the Nazi party early in his career in order to keep his orchestra position and professorship. Of course as most German’s, he later became disillusioned with the course his country was taking. When retired he had no pension, so he worked as a coal man, delivering coal for heating. He was apparently forgotten by the government and musical establishment, even though his students were scattered across Europe in the most important musical posts, though many were in military bands because of the war.

He was a very strict teacher and started lessons at 8AM every morning and expected his students to be on time. He and his students would start every day playing long tones to develop good sound and power in all registers. Then lip flexibility and tonguing exercises, followed by scales and arpeggio’s in two octaves from memory and finally etudes and solos. He used Robert Muller’s Technical Studies for Trombone, Volumes 1-3.

His ideas on the use of the body in playing sound strange to us today. He said, “nobody can see what a brass player is doing inside his mouth. Here are the secrets: what you do with your tongue in articulation, how you shape it, how you use your jaw, the space in your mouth, the air pressure, etc. Then come other secrets in using the body for playing like a certain tightening of the buttock muscles for certain high notes, because this will open the throat (glottis) to make to sound come out full and loud, and then expand the nostrils on certain high notes to give support and relieve fatigue or add power. Even raising the eyebrows on certain notes or passages. Embouchure control is not only the muscles around the mouth, but a correct distribution over several face muscles and throat muscles.”

One of the interesting features of teaching in that place and time was the fact that famous teachers never gave away the so-called secrets they had amassed until they were retired, and even then only to a few prize students, so the knowledge could be carried on to the next generation. The fear was that the students could take away the livelihood of the teacher.

The following is an except from the diary of Anton Hansen from 1911 after lessons with Paul Weschke in Berlin: “I spent two hours with Paul Weschke at the academy. He has an excellent embouchure in the high and low register, but he said that one day without practicing can weaken it. He always started with long tones. Then I played Klughardt’s Romance. Then I asked him to play David’s Concertino to my piano accompaniment. He played it splendidly, showing great strength and endurance. The trills were superb, but the legato was not good. His technique in the cantabile passages is quite wrong, because he slurred notes with the jaw instead of slurring with the tongue. When Weschke asked me for my views, I told him honestly what I thought about his performance. I added that in the Royal Orchestra (Copenhagen) we had a great trumpet player, Thorvald Hansen, who was my ideal, and if he could combine his fantastic technique with Hansen’s blowing technique, his playing would be perfect. I gave him my opinion, and to his credit he was surprisingly interested. When we had finished the David, I ventured into asking him to play some studies which I was not able to play myself and told him of the doubts I had about my abilities as a trombonist. I had thought that scales played fast and legato could sound the same way as on a valve trombone, but it was clear that Weschke, while he could play the scales fast, he could not play them legato in the true sense of the word and I was relieved of a worry which had burdened me for years. During the ensuing discussion on the imperfections of the slide trombone, he said among other things that we must remember that every instrument has it’s own characteristics. Things that can be played on the piano can be unplayable on the harp, and vice-versa, and a child of 8 can play a passage on the piano that is impossible on the trombone.

Some interesting facts about Paul Weschke’s playing career:

- He played a Bb trombone on the majority of works in solo and opera.

- He played a trombone in C when playing operas in alto clef, such as Wagner’s Lohengrin, but used the same mouthpiece.

- He played alto trombone in Eb in old operas like Magic Flute with the same mouthpiece.

- He apparently could play up to double high Bb and practiced 4-5 hours daily.

- He could play all the notes of the valve register with a full sound and tone quality without a valve.

- At the opera they did not play the difficult passages for valve trombone in such operas as Othello, Falstaff etc.

- He was very expressive in his solo playing, with a strong vibrato. In David’s time the tradition was no vibrato at all.

- Weschke was more of a showman than a classical musician according to Anton Hansen.

- Weschke was able to master multiphonics, as in Robert Muller’s Techinical Studies.

Photographs

all materials from the Per Gade collection

Paul Weschke with his custom made trombone from Edward Kruspe: “Model professor Paul Weschke”. No. 21.

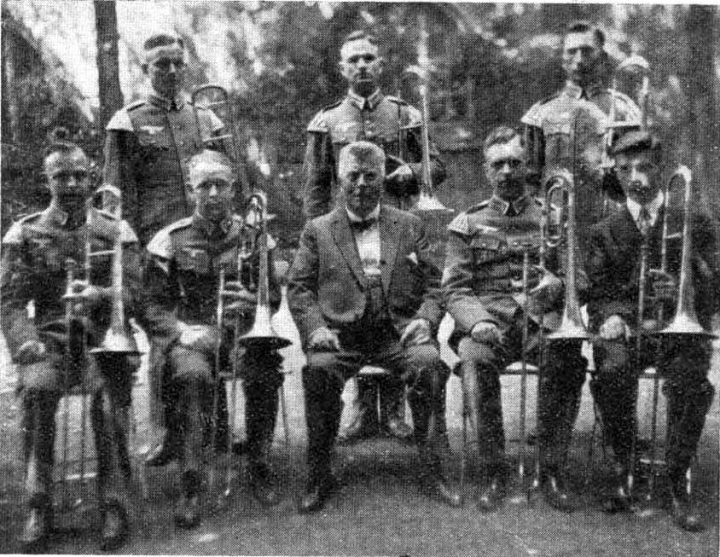

Paul Weschke with some of his students from military bands.

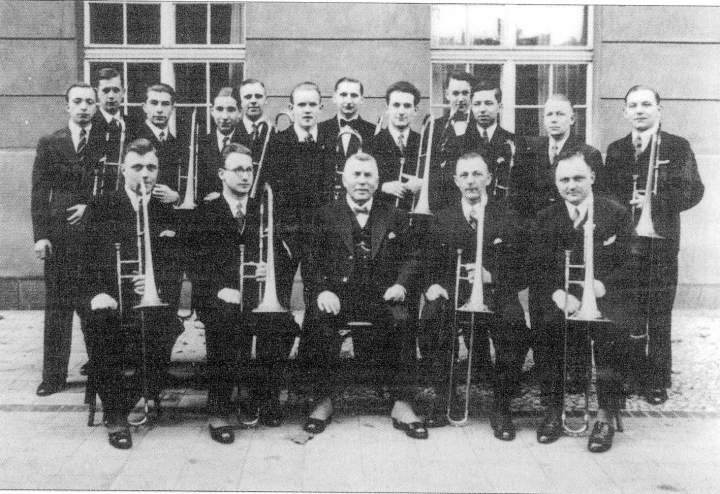

Paul Weschke with some of his students (classical music) in Berlin, circa 1936-39.

Paul Weschke 1936 (4 years before he died).

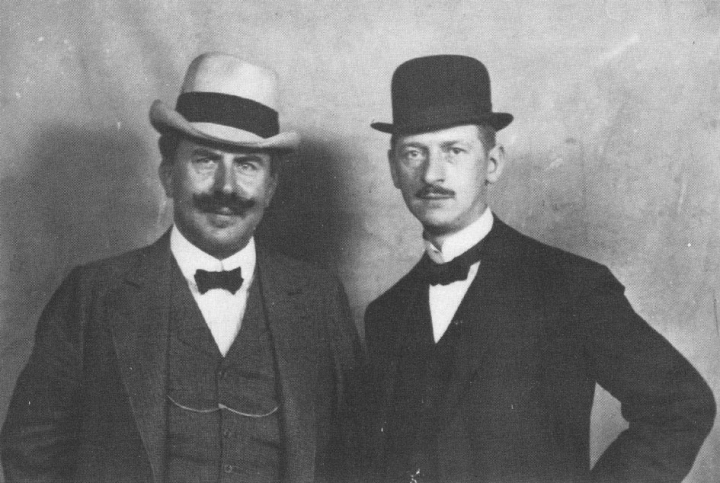

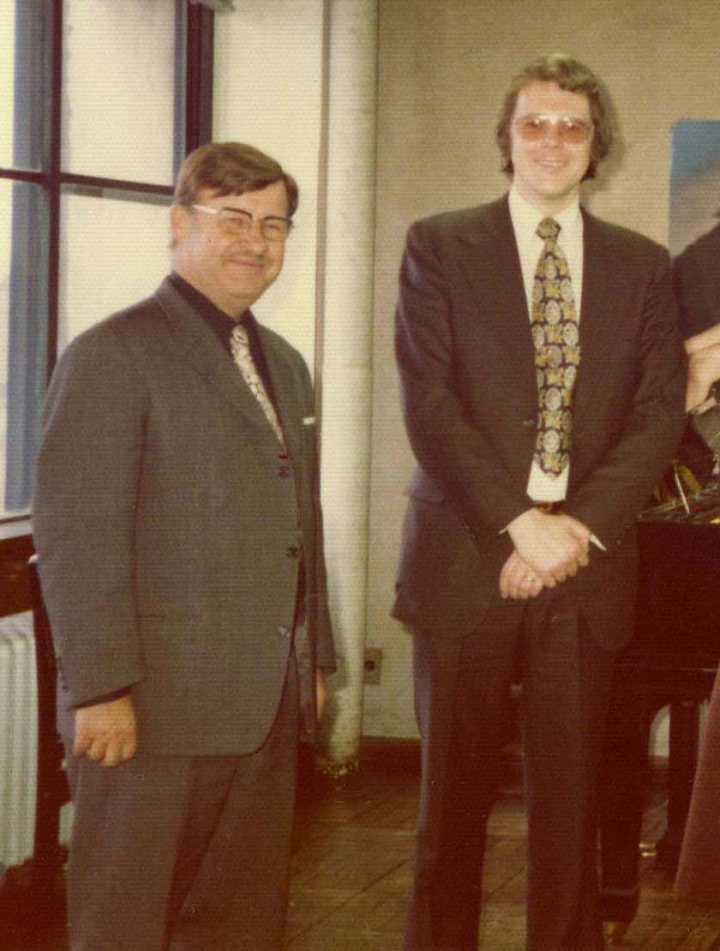

Paul Weschke with solo trombone player Anton Hansen (The Royal Opera & Ballet, Copenhagen. Denmark). Photo from Berlin 1911 (before 1st World War). Weschke was 44 years old on this photo.

Edward Kruspe’s alto trombone in Eb.

Ed. Kruspe’s Bb trombone “Model professor Paul Weschke” No. 21.

Ed. Kruspe’s Bb trombone “Model Virtuoso” No. 22.

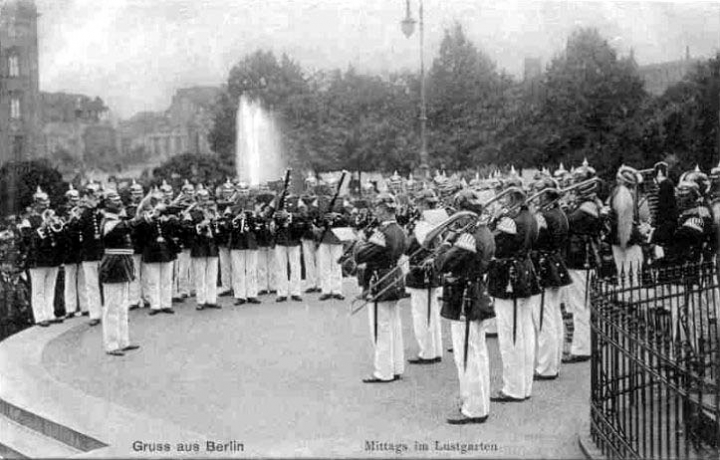

German military band. Beginning of 1900 (before 1st World War), all Kruspe horns.

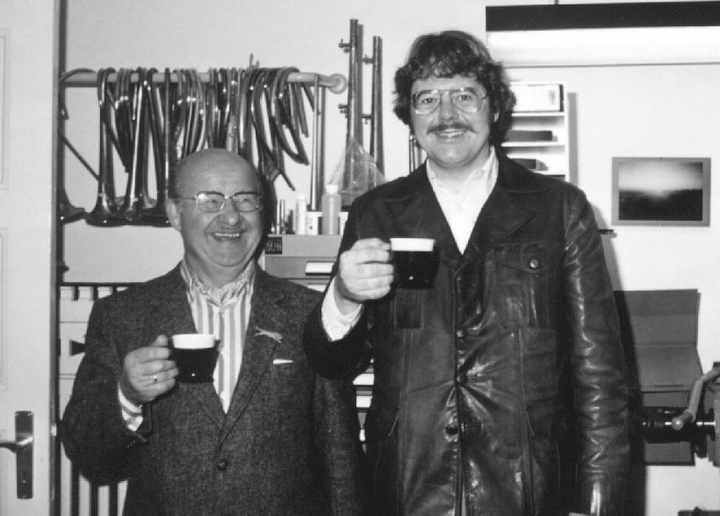

From left: Professor Kurt Putzke, formery NDR Symphony Orchestra, Hamburg (he was a pupil by Paul Weschke) together with professor Per Gade. At Hamburg, Germany, autumn 1983. Old friends meet again.

Professor Kurt Putzke (pupil by Paul Weschke) and professor Per Gade. In Tokyo 1972. (Also Per Gade’s 1st wife, the pianist Masae Iwamoto Gade).

Professor Kurt Putzke (pupil by Paul Weschke) and professor Per Gade. In Tokyo 1972.

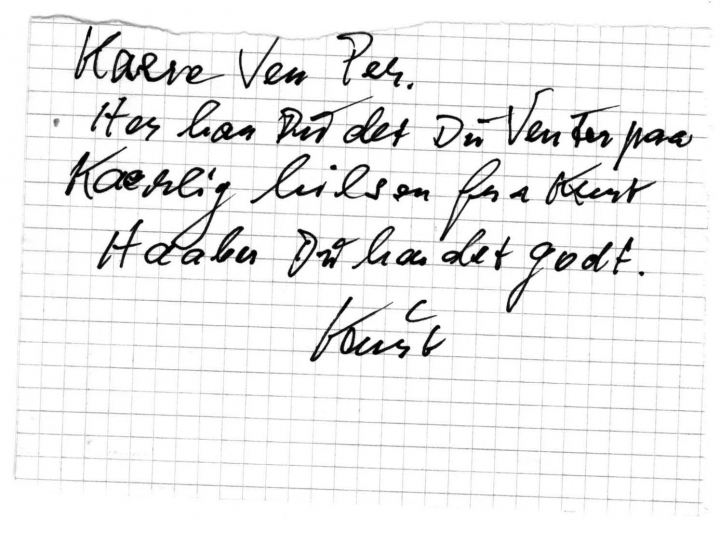

Small note from professor Kurt Putzke to Per Gade: (He was a language talent, spoke several languages including Danish, a language he learned as a dance band musician performing in Denmark between the two world wars).

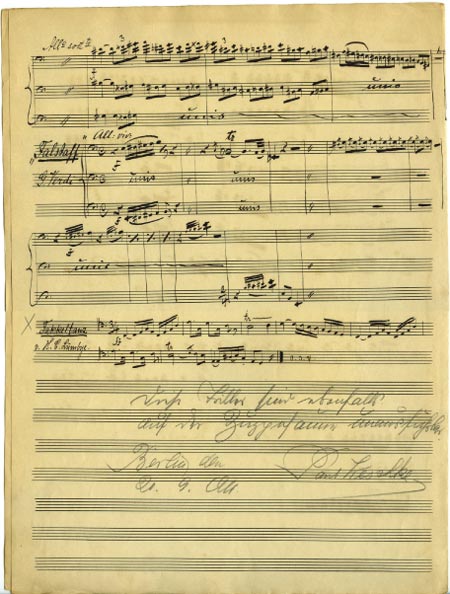

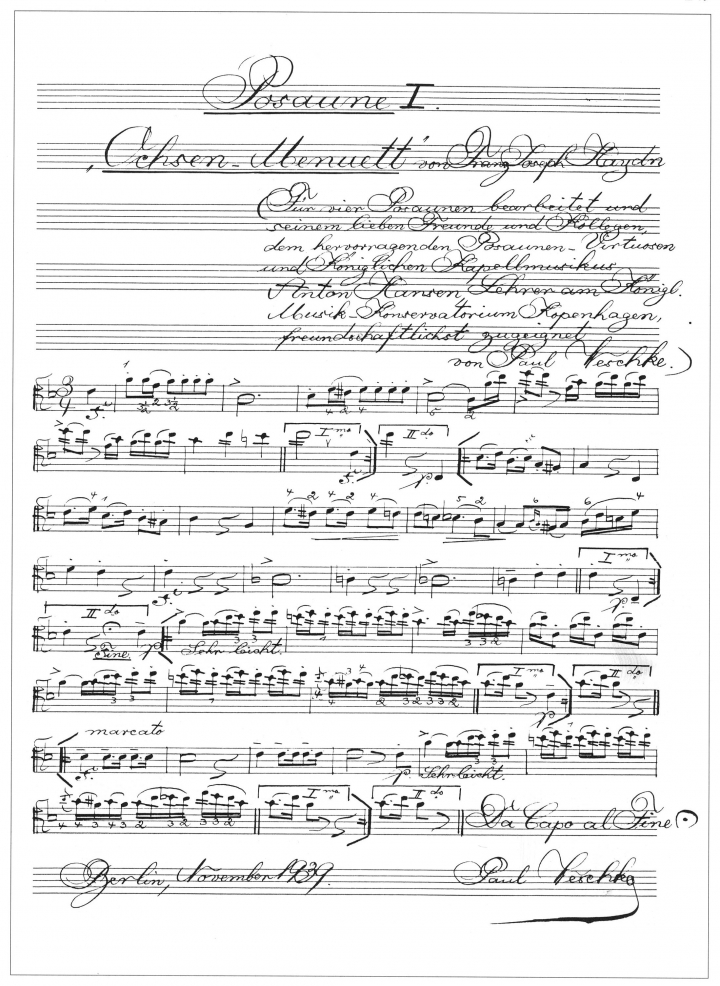

This is the hand writing by professor Paul Weschke. 1939 A transcription for trombones, music by Fr. J. Haydn’s “Achsen Menuet”. As a “thank you” for food parcels. Written only four months before Paul Weschke died.

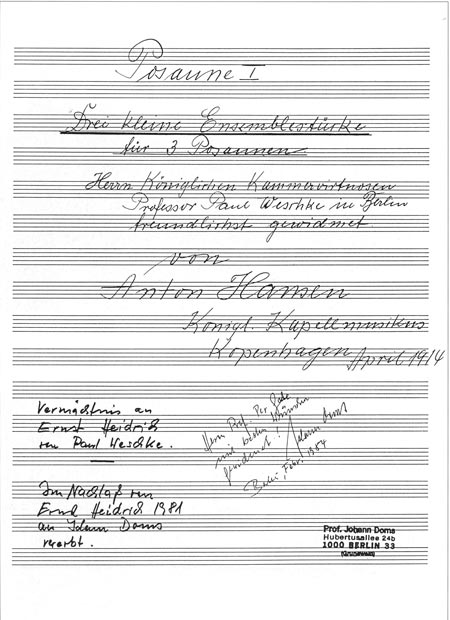

Handwritten excerpts from the orchestra repertoire: The handwritten notes at the bottom is by Paul Weschke (in German) 1911.

Handwritten music from Anton Hansen to Paul Weschke. 1911 “3 Small Ensemble pieces for 3 trombnes”: Per Gade got this from solo trombone player in Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra Johann Doms, who got it from the man who got all printed music from Paul Weschke when he died in 1940.